Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), often called "forever chemicals," have been widely used for decades in everything from waterproof clothing and food packaging to firefighting foams and non-stick cookware due to their exceptional ability to repel water and oils. However, these chemicals persist in the environment for centuries and accumulate in human bodies, with growing evidence linking them to serious health problems including cancer, developmental delays in children, and reproductive issues. This creates an urgent need for scientists and engineers to develop alternative materials that can match PFAS performance in critical applications like medical devices, protective textiles, and water filtration systems, while being safe for both human health and the environment. The challenge is significant: researchers must create surfaces that repel liquids as effectively as PFAS-based materials, but without the persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic properties that make PFAS so problematic.

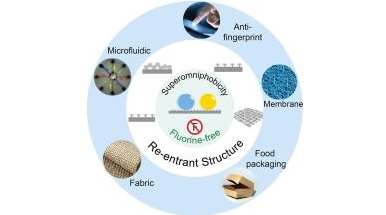

In the review article "Non-fluorinated superomniphobic surfaces" (DOI: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2025.101581) published on Progress in Materials Science (Elsevier, Impact Factor 40, 2024 Journal Impact Factor, Journal Citation Reports (Clarivate Analytics, 2025), the authors provide a comprehensive overview of recent PFAS-free strategies for achieving superomniphobicity. The review discusses both texture- and chemistry-based approaches, offering a clear perspective on current challenges and emerging opportunities for creating sustainable, high-performance, PFAS-free superomniphobic surfaces.

Prof. Carlo Antonini of the Department of Materials Science, University of Milano-Bicocca, carried out the study during his sabbatical at the Department of Mechanical & Industrial Engineering, University of Toronto (Canada), in collaboration with the research group of prof. Kevin Golovin and a colleague now at the University of British Columbia.